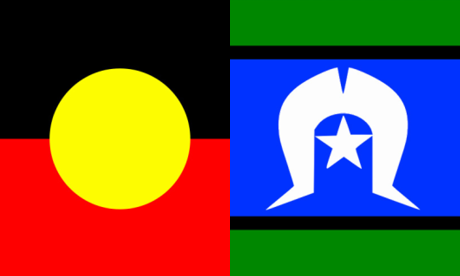

There is no one-size fits all approach to indigenous housing. The needs of remote communities are not that same as those in urban areas. What is common across the board is the impact of bad government intervention.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders make up 23% of homeless persons, but represent 3% of the population. The vast majority of Indigenous homelessness is due to severe overcrowding (which is considered as a form of homelessness).

At StreetSmart, we work to mobilise resources for critically underfunded homelessness initiatives. Our partners in the Indigenous sector tell us they have fight tooth and nail to get the government to invest in their work. The money is there – with investments like the Remote Housing Partnership worth $5.4 billion. But it doesn’t ‘trickle down.’ Read More

In 2011 the WA government implemented a ‘big stick’ approach to public housing evictions. Because Indigenous people are more likely to require public housing, and more likely to have complex issues – the practice has meant more Indigenous evictions. The First Nations Project have proven that the big-stick is unwarranted. By providing the assistance a family needs, like property maintenance and psycho-social support they need. The Project has prevented 100% of evictions and achieved this result with an army of volunteers and very little funding. When the taxpayer bill for every eviction is $40,000 and comes at enormous cost the family, we have to ask – who is it really helping?

In 2011 the WA government implemented a ‘big stick’ approach to public housing evictions. Because Indigenous people are more likely to require public housing, and more likely to have complex issues – the practice has meant more Indigenous evictions. The First Nations Project have proven that the big-stick is unwarranted. By providing the assistance a family needs, like property maintenance and psycho-social support they need. The Project has prevented 100% of evictions and achieved this result with an army of volunteers and very little funding. When the taxpayer bill for every eviction is $40,000 and comes at enormous cost the family, we have to ask – who is it really helping?

As we wind up another year, it is a good time to pause and reflect on where we have come from, and where we need to go. Sadly, 2017 has not been a positive year for the state of homelessness. We have continued to backslide on key issues like affordable housing, and maintained the status quo in key funding areas. While government has failed to act, 2017 has also seen increasing public concern, and greater media reporting on the causes and harms of homelessness.

As we wind up another year, it is a good time to pause and reflect on where we have come from, and where we need to go. Sadly, 2017 has not been a positive year for the state of homelessness. We have continued to backslide on key issues like affordable housing, and maintained the status quo in key funding areas. While government has failed to act, 2017 has also seen increasing public concern, and greater media reporting on the causes and harms of homelessness.

The Bad Love Club

The Bad Love Club